On July 28, 2011, Jerry Eagan and myself crossed over into Northern Mexico. This was the first stage of our journey to “the Canyon.”

In March 1886 Geronimo and what remained of his Chiricahua Apache followers met here with Gen. Crook of the US Army to discuss terms of surrender.

The meeting was notable for three reasons:

1) It was a failure. Some members of the “gang” surrendered, but Geronimo and what would be known as the “last holdout band” made a break for it and headed into the wild country.

2) Gen. Crook insisted that three interpreters be employed during his discussions with Geronimo and the others in order that the most accurate record possible might be made of the encounter. This record remains today – a remarkable instance of historical documentation and a rare opportunity to gain more direct insight into these characters’ motivations and thoughts. Geronimo, for example, reveals he is puzzled as to why so many people in the United States want to hang him. Crook, meanwhile, makes no secret that he considers Geronimo a total liar.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, 3) C. S. Fly, a photographer from Tombstone requested permission to join the expedition in order to photograph Geronimo and capture what he considered to be saleable images. Fly’s photos would become the iconic illustration of Geronimo’s outlaw persona. Few people realize that these photos are the only photographs ever taken of American Indians posed as “hostiles,” still under arms and in the field. (Typically, photos of American Indians represent them long after they have been taken captive – in costume, playing the warriors they had once been.)

Many of my colleagues and friends felt that it was foolhardy for our team to attempt the journey to this place.

Traveling in the borderlands of Northern Mexico right now is extremely precarious, unfortunately, due to extreme violent activity that creates a climate of fear in the region. Certainly, danger was always with us in our journey. However, with the support of individuals living in the state of Chihuahua, we were able to make it there and back safely.

Anyway, it was important for the film, and for me, to have this climactic scene. If you’re making films about Apaches…you can’t not brush with a bit of danger. We went in to get as close to the experience of the late 19th century as we could possibly get, knowing that it would be quite possible to end up in a patch of weeds.

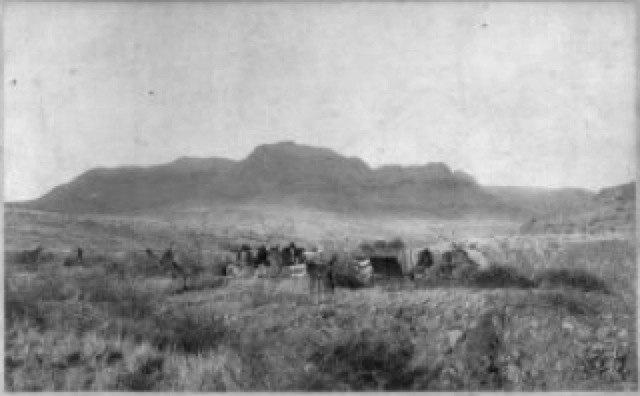

None in our party had ever been to this place before, except Jerry. And even he didn’t have a clear memory of the dirt roads we needed to take. Sections of the road were boulders. It was a hard journey – about an hour off a paved road. At one point we encountered a vaquero on his horse who seemed much better equipped to deal with the rough terrain than we were in our non-four-wheel drive vehicle. He offered initially to guide us to the canyon – and then for no apparent reason, changed his mind. Eventually we found ourselves before the mountains, which, thanks to Fly’s photographs, proved we were in the right spot.

Just beyond the canyon, we stopped at a small farm house, where a blond woman wearing a filthy Mickey Mouse t-shirt marched over to us and began speaking in English. She knew the history of the ground and had two children hanging onto her. I noted this encounter as a strange contrast to the mythic “end game” I associate with this place. A bit hallucinatory almost.

I should credit my intrepid guide and subject, Jerry Eagan, who was really responsible for the effective planning of the trip. Despite previously expressed concerns about “reentering Indian country” – as the enemy territory was sometimes referred to in Vietnam – and taunts that I was romanticizing danger – he led the way.